Why can’t the landlord just raise the rent to cover the tax?

Georgism makes a simple pitch: we will replace all taxes with a single tax on the unimproved value of land. Everyone will live in harmony and sing kumbaya and all of our problems will be solved.

But savvy readers will probably ask the question: won’t the landlord just raise the rent to pass the tax along to the renter and mess the whole thing up?

Apparently, a Land Value Tax is one of the few taxes that cannot be passed onto the consumer! This is due to that special quality of Land: fixed supply. It turns out that taxes can only be passed on to consumers when the producers are able to reduce supply.

The way most taxes work

We’re used to the idea that taxes get passed onto the consumer. Take for example a tax on cigarettes:

Say a pack of cigarettes costs $10. The government wants to discourage smoking, but doesn’t want to punish the poor smokers directly. They want to stick it to Philip Morris and Co.

So they impose a $5 tax on every pack of cigarette produced.

Will imposing the tax on production shield the consumer?

Of course not! Philip Morris will just raise the price to $15 and the consumer will pay it.

Why can the producer do this?

We’re all used to seeing a supply and demand curve and nodding off. I studied economics and I still find this a little confusing and unintuitive.

The only thing you need to keep in mind right now is the common sense idea that when price goes up, fewer people want to buy that thing. If a pack of cigarettes was $1,000 a lot fewer people would buy it.

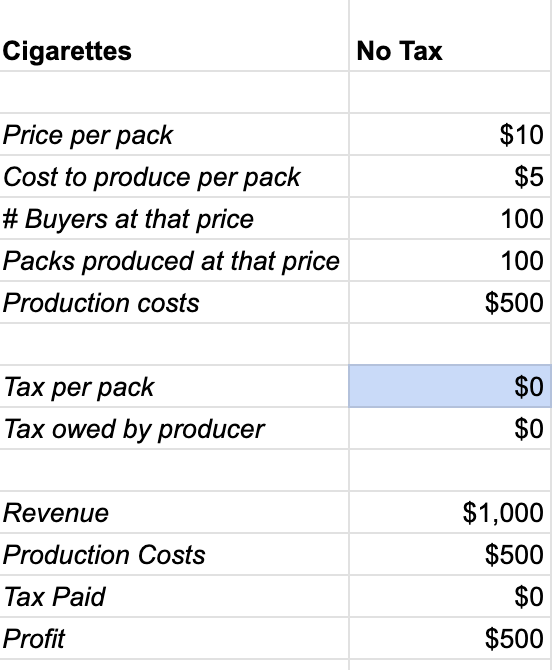

Scenario 1: No tax

At $10 a pack, 100 people will buy. Revenue will be $1,000 (100 packs times $10/pack).

Production costs will be $500 (100 packs times $5/pack).

Taxes are $0.

Profit is $500 (Revenue - Production costs - Taxes).

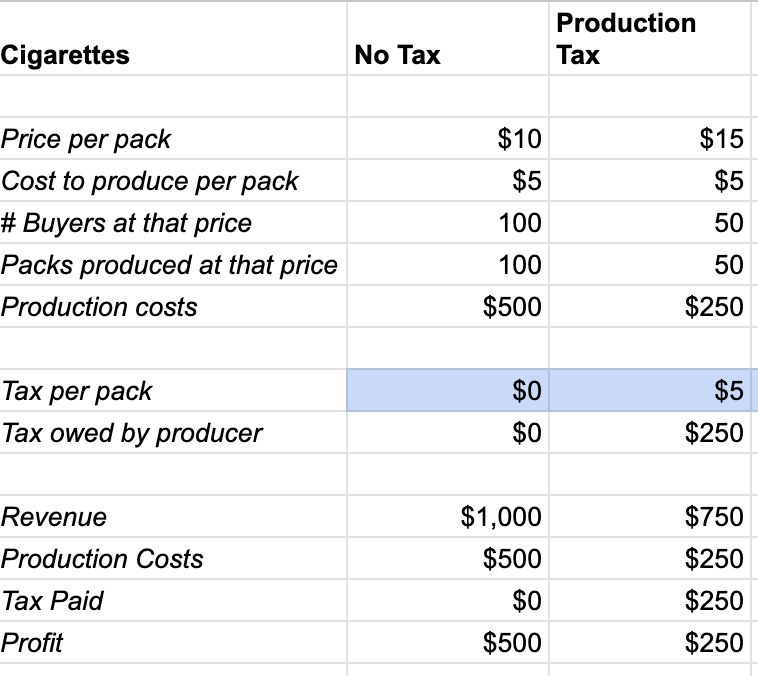

Scenario 2: Let’s add a production tax

Let’s add a $5 tax per pack produced:

The cigarette company can pass this tax onto their consumers by raising the price of cigarettes by the amount of the tax (i.e. from $10 to $15).

At $15 a pack, only 50 people will buy. Revenue will be $750 (50 packs times $15/pack).

Production costs will be $250 (50 packs times $5/pack).

Taxes are $250 (50 packs times $5/pack).

Profit is $250 (Revenue - Production costs - Taxes).

Philip Morris has successfully passed 100% of the tax onto the consumer. Philip Morris does suffer - their profits drop by 50%. But the consumer pays the full increase of the tax.

They can get away with this because they reduced supply. That is, they raised the price which reduced demand to 50. But since they only had to pay taxes on the packs they produced, their tax bill was reduced by raising the price.

The manufacturer will still produce under this tax regime. They’ll probably vote Republican and write to their senator, but they are making $250 in profit - which is still profit.

What if the cigarette manufacturer couldn’t reduce supply though

Imagine an admittedly bizarre scenario where the CEO of Philip Morris makes a pact with the devil. The devil says “You MUST produce 100 packs of cigarettes NO MATTER WHAT or else I will come after you and your family.”

The CEO of Philip Morris isn’t a monster. So they do the devil's bidding and make 100 packs no matter what.

Scenario 3: A production tax, with fixed supply, and trying to pass it onto consumers

The producers try the Scenario 2 trick of raising prices to $15. What happens?

At $15 a pack, only 50 people will buy. Revenue will be $750 (50 packs times $15/pack).

Production costs will be $500 (100 packs times $5/pack). Remember the pact - they must produce 100!

Taxes are $500 (100 packs times $5/pack).

Profit is now negative at -$250!

Why didn’t that work?

This is because at a higher price, demand for cigarettes drops from 100 to 50. Revenue drops. But with fixed supply, both the cost of production and taxes are charged at the rate of 100.

And actually, the more I raise prices, the deeper in the hole I go! Because by raising prices but not reducing production, I am just reducing the pool of people willing to buy my product. And I am driving revenue down and down. But my costs stay fixed because of the tax.

How could Philip Morris break even under the demonic fixed supply scenario? Counterintuitively, they can do so by lowering the price! If they lower the price, they at least sell more cigarettes. And that allows them to break even.

Scenario 4: A production tax, with fixed supply, and not passing it onto consumers

When the price of a pack of cigarettes drops from $15 to $10, 100 people want to buy it. So revenue jumps from $750 to $1,000. And now the producer is at least breaking even. Whereas before they were losing -$250 per year.

Hopefully it’s now clear that you can only pass a tax onto consumers when you have the ability to reduce supply enough to offset the tax.

Would this happen with land?

Remember that Land is Special. The quantity of land is fixed: you can’t make more of it.

But you also can’t make less of it! And that is why a land value tax cannot be passed onto renters.

So land is like the demonic fixed supply scenario. A landlord must pay the tax no matter what - just for owning it. So if they try to raise the rents on their land, they will drive down revenues without being able to correspondingly “cut production” of their land to dodge the tax.

I own a property that I can rent for $12,000 per year. If I pay no tax, that means I am making $12,000 a year in sweet sweet profit.

But the government comes and says I am going to tax you for 100% of the annual income that land is capable of generating just for itself. So that price will be $12,000 in taxes.

Clever landlord that I am, I think I’ll just raise the rent! So I do and now I say the rent is $18,000.

But that piece of land is capable of generating $12,000 per year and not a penny more. So no one is willing to rent it at $18,000. The landlord still has to pay $12,000 in taxes, but they make $0 in profits because there is no renter for them at that price.

Unlike the cigarette manufacturer they can’t reduce production to dodge the tax. The only way they can break even is if they lower the price back to the original cost.

What if the landlord raises the rent but says it's due to improvements?

A smart reader asked, "well can't the landlord raise the rent but tell the government they are doing so due to improvements?"

It's a good question!

The average landlord is already charging the maximum that the market will bear in rent. They can raise the rent for any reason they want to. However, if they raise the rent without corresponding improvements, the demand for their land will fall because the price went up for the same quality of service.

This reduction in demand means less revenue for the landlord. However, the landlord must pay the tax even if they earn no money from it. So they will want to lower the price back to the market rate so that they can make enough money to pay their tax bill.

Another way to visualize this is that today, holding Land has approximately zero cost for the landlord. A Land Value Tax would place a cost on holding onto land. And therefore the landlord needs to use the land at a certain rate in order to cover their costs.

Is this fair to landlords?

This may seem like a raw deal to landlords. But we must remember that Property = Land + Improvements.

Let’s say our example landlord wants to earn more from their land so they actually turn a profit. All they need to do is improve their property.

As a simple example they can add a second unit. Now their property has 2 rental units. The Land's underlying value is unchanged so the Land Value Tax is still $12,000.

If the landlord charges $9,000 per unit, they will make $6,000 in profit! They make $18,000 in revenue (2 units at $9,000 per unit) and pay $12,000 in taxes.

Everyone is better off!

Each renter only pays $9,000 per year instead of $12,000 because of increased supply.

The landlord makes $6,000 in profit instead of $0 or negative profit.

The government earns $12,000 in revenue to redistribute to the citizenry!

Further reading

So under the Land Value Tax a landlord cannot pass the tax onto their tenants. But they can increase their profits by improving their land. This drives down rents.

But you don’t need to just trust this theoretical framework. Apparently, there are real world examples and studies of this happening in practice. If you’d like to read more about it, check out this awesome article about the empirical results of Land Value Taxes on rents.